At a glance, the rusty, faded sign with a crumbling concrete wall to one side and a neighbouring, decrepit corrugated tin shack to the other, really wouldn’t give the impression of being a place where great work is happening. But as we all know, looks can be deceiving.

Set in the heart of Diego Suárez in northern Madagascar, a dusty town with dilapidated colonial buildings lining the streets, is Diego Suárez High School which a year ago, The Ladybug Project began funding.

7.15 am and a steady flow of Malagasy students, clad in light blue tunics, indicated the start of the school day. There was a slight coolness in the air as a result of the gentle breeze but it wouldn’t be long before the heat of the day set in.

The children congregated outside their respective classrooms, chatted away energetically to each other; some retrieved exercise books from their bags ready for their homework to be inspected by the teacher before they were permitted to enter the classroom; others sat briefly in the shade of one of the trees or perched on the wall frantically completing the homework assignment that should have been done the night before.

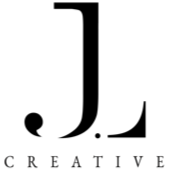

The first students in the classroom swept the dust and leaves out of the room whilst the others were queuing to get their homework approved. With 94 pupils in the class, it wasn’t a speedy process! The rickety, wooden desks with attached benches had just enough space for three and, as the students trickled in slowly filling the classroom the lesson commenced. English was the subject for the next 2 hours. The topics were ‘Introductions’, ‘Numbers’ and ‘Classroom Objects’. The learners listened attentively to the teacher, repeating phrases, answering questions and copying words and sentences neatly into their exercise books when required. The children were all keen to learn and their thirst for knowledge was clearly visible.

With no electricity at all in the school, the room was lit by the sunlight streaming through the open door and the three large windows, which were without panes of glass, and instead had horizontal rusty metal bars. This openness enabled the welcome breeze in. This kept the air in the room fresh, but with it also came the dust and leaves from the central courtyard.

The state of the school was in desperate need of attention, not having been renovated since Madagascar was given Independence back in 1960. Big cracks ran down the crumbling concrete walls, the remaining patches of paint on the walls were flaking off and a long, well-used blackboard, on which it was hard to see the chalk writing, dominated the wall space at the front of the room. Panels in the flimsy ceilings were missing, exposing the patchy corrugated tin roof above. It began raining lightly during the lesson and much of that rain found its way through the holes in the ceiling into the classroom and onto the pupils inside. A torrential downpour during a lesson I’m sure must be a nightmare for pupils and teacher.

The communal areas didn’t really offer much more comfort. During break times, apart from gathering under the handful of trees on the premises, there is minimal shelter from rain. There are two basketball hoops but no sign of any balls. No running water meant that there was no drinking fountain, or facility to wash hands and the squalid state of the long drop toilets was abhorrent.

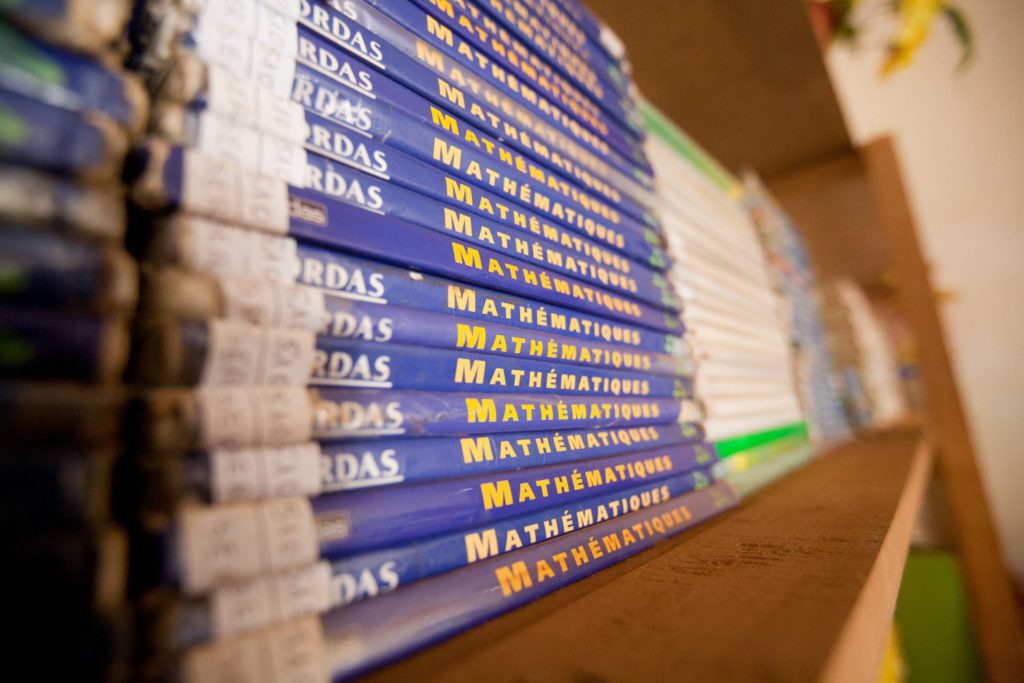

Madagascar is amongst one of the poorest countries in the world and its education system is in dire straits. Two years ago the government cut funds to education by 30%, and because of the political unrest, many of the western countries have withdrawn all non-essential aid. As a result the education system has suffered tremendously. Schools have had to continue without basic resources, regular teacher pay and with facilities that should be condemned, so it is critical that NGOs, like “The Ladybug Project”, continue the good work that they do.

Much still needs to be done, and already a year in The Ladybug Project has achieved a lot and, subject to funding, will hopefully continue to do so. Next summer they hope to work with school and city officials and will begin by tackling the easier things first: build enough desks for each classroom; replace blackboards in all rooms; heavily renovate the “bathroom” facilities; patch up concrete and rebuild broken walls; re-paint the school; undertake training projects with the teachers. Next on the agenda are the bigger issues like supplying the school with electricity and running water.

The headmaster of the Diego Suárez High School has great visions and hopes for the school and is working closely with The Ladybug Project but is aware of the reality that everything boils down to funding and that will take time.

In the meanwhile, he continues to ensure that his teachers are providing the best education possible for the students with their severely limited resources. However, with a total of 1510 students in the school and just 14 classrooms most of the class sizes exceed 100. The minimal resources and facilities that the school has are overstretched and inadequate.

The school and its students are not looking for pity. They want the opportunity to learn and in turn this will give them the ability to have an education which will give them a great start for life. A difference to the lives of the students is being made here; children are learning.

0 Comments